The New Teacher Underground is a social space for new and alternatively certified teachers to find support and dissect the current realities of education in NYC. On October 14th from 5:30-7:30 we will come together for the first time since our weekly summer sessions with a happy hour discussion focused on the racial disparities of teacher recruitment practices in New York City. We will also have time to share stories and experiences from the first weeks of school. We hope you can join us!

The New Teacher Underground

Friday October 14th, 5:30-7:30

Upstairs @ Lolita Bar, 266 Broome Street at Allen

B/D to Grand, F to Delancey, J/M/Z to Essex

We will start the happy hour with an opportunity for folks to take a look at and discuss a piece by UFT Vice President Leo Casey called “Talking About Race, Teachers and Schools: How I Found Myself Featured in Right Wing Conspiracy Theory”… The entire piece can be found

here, though we will be focusing on the section entitled “Talking About Race” which is pasted below.

Talking About Race

… Let us start with the facts on the changing racial and ethnic composition of the teaching force in New York City public schools. In 2009, members of our Delegate Assembly brought to the body a concern about declining numbers of African-American and Latino teachers in New York City public schools. The UFT saw this question as a serious one, not to be taken lightly or used for some political advantage. For us, it was a question that was both an educational issue — there is a solid consensus in the education research that a diverse teaching force has positive educational benefits for both students of color and white students — and an issue of racial justice — the teaching force should be fully integrated, just as the armed forces are, yet African-American and Latino teachers are dramatically underrepresented in our schools. In response to the concern brought to it, the Delegate Assembly passed a resolution mandating the union to investigate the issue and report back to it with findings and recommendations. Then UFT President Randi Weingarten appointed a committee to undertake this work, and asked me to co-chair it with one of my retired predecessors as UFT Vice President for Academic High Schools, John Soldini.

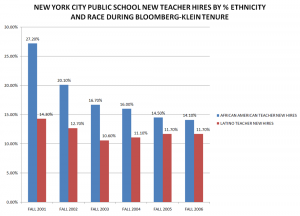

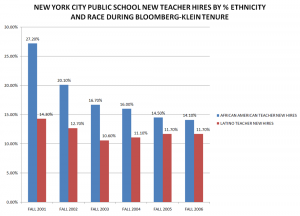

Our committee researched the issue, and compiled data from New York State, New York City and other sources. As laid out in our report to the UFT Delegate Assembly, we found that there was a decline in the numbers of African-Americans and Latinos being recruited to teach in New York City public schools, a most serious problem in a field where they are significantly underrepresented. There are many ways in which this could be established, but the most unassailable method is with the NYC Department of Education’s own numbers.** In the 2000-01 school year, the last year before Joel Klein assumed full control of the public schools, the percentages of new teachers were at 27.2% for African-Americans and 14.3% for Latinos. As the accompanying chart shows, there was a dramatic decline in these numbers during the Bloomberg-Klein years — including an almost 50% decline for African-Americans.

Our committee went about its work in a careful and deliberate way. Since the NYC Department of Education under Bloomberg and Klein had come to rely heavily upon the NYC Teaching Fellows and Teach for America [TFA] for recruiting new teachers, we decided it was important to determine what role, if any, these programs played in the decline of African-American and Latino teachers. We asked the then head of the New York City office of Teach for America, Jemina Bernard, and the NYC Department of Education official responsible for oversight of the Teaching Fellows program, Vicki Bernstein, to meet with us, so we could learn first-hand about the role their programs played in teacher recruitment. The results of our investigation were not entirely what one might have expected. We found that the cohorts of NYC Teaching Fellows reflected the demographics of the teaching force already in place: while this program was not a force for furthering the integration of the teaching force, it was also clearly not driving the declining numbers of new African-American and Latino recruits. The numbers for Teach for America told a different story: the national demographics published on the Teach for America web site, which we were told by TFA officials reflected the numbers in the NYC TFA cohort, had percentages of African-American and Latino recruits which were much lower than even the declining numbers under Bloomberg and Klein: in 2010, for example, African-Americans recruits were 11% and Latinos were 7% of the TFA cohort. The composition of the TFA cohorts in New York City was clearly part of the problem in the declining numbers of African and Latino teaching recruits.

… The difference between the Teaching Fellows cohort and the TFA cohort was, our committee discovered, an artifact of where they recruited. The Teaching Fellows took many of their recruits from public universities, predominantly the City University of New York and the State University of New York, while TFA recruited almost entirely from elite private universities, with Ivy League schools playing a major role. The racial and ethnic composition of the public universities is much more diverse and representative than that in elite private universities, so the Teaching Fellows were drawing from a pool which had many more potential African-American and Latino recruits. (For those who know their educational history, this pattern is not that surprising: the move to establish the state university system in New York after World War II drew its strongest advocates from the African-American community, which saw it as providing an access to higher education they had not been able to achieve with private universities.)

The difference between the Teaching Fellows and TFA led the committee to a recommendation which at first seemed counter-intuitive to us. We had initially thought that greater recruitment in historically black colleges could be part of the answer to creating a more diverse teaching force. Upon investigation, we found that the programs of study in most of those institutions and the small size of their graduating classes would not yield the numbers of potential recruits which could make a real difference in a teaching force the size of New York City. Rather, recruitment needed to be focused on public universities, as they had both large graduating classes with appropriate majors and significant concentrations of students of color. We prepared a resolution with our recommendations, and it was vigorously debated at our Executive Board and at the Delegate Assembly, which voted overwhelmingly to adopt it in January.

… Whatever our background, all teachers enter this profession to make a difference in the lives of children. The issue lies in the policy decisions, made by those in power in institutions like the New York City Department of Education and Teach for America, that skew a teaching force away from the goal of diversity and racial integration which best serves the educational needs of students and the societal ends of racial justice.

What is particularly disturbing about the New York City public schools under Bloomberg and Klein is that the declining numbers of African-American and Latino teachers is not the only area of racial and ethnic integration where our schools are going backwards. The very low numbers of African-American and Latino students in the city’s elite specialized high schools — Stuyvesant, Bronx Science and Brooklyn Tech — have been declining, and the one modest program that the Department of Education sponsored to increase racial integration and access for students of color, the Specialized High School Institute, has been undermined in that task by the regular reorganizations of the DoE structure and New York City’s unwillingness to fight a law suit which struck at the very heart of its ability to aid the students excluded from these schools. A reorganization of the city’s Gifted and Talented Programs in elementary schools led to a decline in the numbers of African-American and Latino students served by those programs. The claims of the New York City DoE that results on standardized state tests showed that the achievement gap between students of color and white students was narrowing were questionable from the start, but went up in a complete cloud of smoke when the grossly inflated scores on the state tests were re-normed and all the counterfeit gains disappeared. It is now abundantly clear that under Bloomberg and Klein, the achievement gap on state tests actually widened.

It is common for the advocates of corporate education reform and the privatization of education, from Michael Bloomberg and Joel Klein in New York City to Adrian Fenty and Michelle Rhee in Washington DC, from Whitney Tilson’s misnamed Democrats for Education Reform to charter school management in the National Alliance of Public Charter Schools, to expropriate the language and seize the moral high ground of the civil rights movement. Joel Klein never tires of saying that education is the civil rights issue of our time, and that those who oppose efforts to remake schools in the image and likeness of corporations are the George Wallaces of our day, blocking educational progress for African-American and Latino students in the same way that segregationist governors stood in the door of the schoolhouse to prevent its integration. I will leave it up to the reader to assess the use of that rhetoric in light of the actual record and practice of those who employ it.

These questions of race, teachers and schools are vital questions, ill-served by feverish denunciations of single sentences taken out of context. In the interests of an open, frank and honest debate, let me make a public offer to appear on the same stage as Whitney Tilson and address them in a serious public debate.

facebook event page: http://www.facebook.com/event.php?eid=284451864917080